by Hugo Rosen

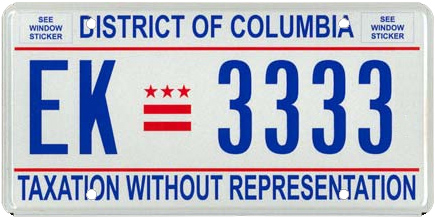

Since its establishment in 1790, the District of Columbia has seen five different government structures, given rise to a Constitutional amendment, and been the subject of numerous legal questions about representation. Our license plate slogan, “End Taxation Without Representation,” expresses residents’ frustration with our limited representation in Congress.

My previous article mentioned three proposals to address this frustration: D.C. statehood, a cessation to Maryland (retrocession), and maintaining the status quo. Today, I will summarize the pros and cons of each proposal and share opinions from across the country on the best course of action. As a D.C. resident, I believe understanding the city’s unique position is crucial to developing an informed opinion, so I’ve tried to be as objective as possible in my analysis of our options moving forward.

D.C. Statehood

The D.C. Statehood plan is rather self-explanatory: It would turn the now-District of Columbia — minus a small federal area on the mall — into a state with two senators and one representative in the House. Many D.C. residents support statehood because it would solve the problem of Congressional representation. “I support statehood; when I am able to vote [representation] will be my top priority,” Lilly, a junior at School Without Walls High School in D.C., told me. Lilly is far from alone: 86% of D.C. residents voted in favor of statehood in a 2016 referendum. The House of Representatives approved a “Washington, D.C. Admission Act” in 2020 and 2021, but the bill has so far failed in the Senate, prompting D.C.’s government to create a website page supporting the proposal.

Most Americans support the idea of representation; everyone interviewed for this article agreed that D.C.’s current political system does not provide adequate representation to district residents. The statehood plan’s main problem is not the representation it proposes but rather the power it would grant to D.C. as an entity. The U.S.’s bicameral legislature gives every state two seats within the Senate regardless of size or population. Admitting a new state invariably shifts the balance of political power in Congress, impacting national policy decisions. The fact that most D.C. residents vote Democrat and that, if admitted, we would be the most left-leaning state in the union has therefore generated significant partisan controversy and remains a major impediment to statehood.

Statehood also raises other, less partisan questions. “If DC were to gain two seats in the U.S. senate, it would build resentment, because no other urban area in the U.S. has that much representation,” said Lucas, a senior at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Virginia. “I’d definitely support giving their house representative voting power and allowing other states rights, but the senate seats require more thought.” D.C. is, in most senses of the word, a city. Although we have a greater population than two U.S. states, Wyoming and Vermont, so do other U.S. cities, like Philadelphia. Statehood, critics argue, would give an already powerful capital city too much influence, stifling voices in other parts of the country.

Gaining admittance to the union has been a complex and controversial process for states throughout history, and D.C. is no different. Inevitably, the D.C. statehood plan would affect the political makeup of the entire nation and so must be examined on the national level. On the one hand, statehood would give D.C. residents political parity with the rest of the country, something we do not currently have. However, adding another “slice” to the Congressional “pie” could make the other slices smaller; D.C. statehood might suppress the voices and policy objectives of our current 50 states. As of now, statehood is unlikely but remains the preferred choice of most D.C. residents.

Retrocession

Under the retrocession plan, Maryland would annex D.C., minus the small federal area, back into itself, gaining back the land it gave up to create the district in 1790. Such action has historical precedent; in 1846, modern-day Alexandria seceded from D.C. back into Virginia. Today, Alexandria residents enjoy full representation within Congress. Modern retrocession would make all D.C. residents citizens of Maryland, with all the privileges (representation in Congress) and responsibilities (taxes, Maryland laws, etc.) thereof. Max, a junior at School Without Walls High School in D.C., is a proponent of retrocession. “Although full statehood would be a better solution, waiting for a Democratic supermajority in Congress or the filibuster to be abolished is incredibly unrealistic,” he said. “[Retrocession] is an imperfect solution but I would rather have full Congressional representation than no Congressional representation, even if it means becoming a Marylander.”

Retrocession offers a middle ground between statehood and the status quo, but it has yet to generate significant support. To put it bluntly, neither D.C. nor Maryland wants to unify. According to a Washington Post-University of Maryland report, only 36% of Marylanders support the idea, while 57% oppose it. D.C. residents, who overwhelmingly favor statehood, aren’t eager either. Matthew Weitzner, a Sophomore at School Without Walls, thinks that “statehood is a better idea [than retrocession], especially because D.C. and Maryland are so different.” Mike, a junior, characterizes it as “a stupid idea.”

While statehood would have nationwide implications, retrocession would primarily affect the D.C.-Maryland-Virginia (DMV) Metropolitan area and should therefore be considered as a local issue. Although it would achieve full representation, actual implementation faces the hurdle of public opinion; various retrocession bills, the most recent introduced in 2021, have failed in Congress, and retrocession remains unlikely in the near future.

Maintaining the Status Quo (Doing nothing)

The Constitution’s District Clause gives Congress exclusive authority over “such district… as may, by cessation of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, Become the Seat of Government of the United States.” As previously discussed, the exigence of this clause was the need for a capital city outside of any state’s control, a home in which the federal government was not just a tenant but an owner. Proponents of maintaining D.C.’s current government structure argue that statehood or retrocession could disrupt the city’s ability to function as a capital. Transportation, police, and schooling would all fall under the purview of a new state with considerable autonomy and not nearly as beholden to Congress as today’s D.C.

What of representation? A central argument for maintaining the status quo (which opponents of statehood also like to use) is that D.C.’s current level of representation is adequate for its unique position in the U.S. After all, the 23rd Amendment gave DC residents a vote in presidential elections, and moving to another state for representation is always an option. Adela, a freshman at Harrison High School in New York, says she opposes D.C. statehood because “Washington D.C. is a unique place, and the capital of the USA should be unique.” Statehood and retrocession also pose some practical legal problems. The 23rd Amendment explicitly gives D.C. three electoral votes. The problem is that the statehood and retrocession plans do not eliminate the District of Columbia; they merely shrink it to encompass a small area of federal land. Under the 23rd Amendment, this tiny region would retain D.C.’s electoral votes, opening the door to a situation where the president and their family, some of the only residents in the shrunken electoral district, could cast deciding votes for themselves. Repealing this Amendment, which requires approval from 38 states, could prove challenging.

Regardless of the challenges associated with change, most D.C. residents believe the current system is insufficient, as evidenced by the overwhelming support for the 2016 statehood referendum. Statehood, though the most widely publicized solution, is not the only one, nor is retrocession. Other options include allowing D.C. residents to vote in Maryland Congressional elections (the bonus population would earn Maryland another representative in the house) or giving full voting privileges to D.C.’s non-voting delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton. All proposals affect different groups and different parts of the country in various ways. As the U.S. capital and home of over 700,000 people, the question of D.C. representation is important nationwide, even if the proper solution remains contentious.