by Hannah Saraf

What were you like in high school? Were you already interested in the law or civics?

In high school, I aspired to be a sports writer at The Washington Post. I was very into my high school newspaper, writing mostly about sports, until I started writing about news and other things. But then I was also covering high school sports for other newspapers, like the local paper. So I really thought I wanted to be a journalist when I was growing up. In fact, I did become a journalist after college, and it was actually covering and seeing my first Supreme Court oral arguments in a case involving the National Football League where I realized that I was doing the wrong thing, that I was covering sports, but I was much more interested in writing and thinking about the Supreme Court. In that moment, I knew I needed to go to law school and that I should stop writing about sports for a living and start thinking hard about constitutional law.

That’s such a great story! Were there any teachers that served as big mentors or role models for you in high school, college, or law school?

In eighth grade, I had a really great US Government teacher, and he made us write our first term paper using mostly secondary sources. But, I just sort of remember vividly that my paper was about Ulysses S. Grant and the Civil War. I remember using William McFeely’s book on Grant, which was probably the best biography on Grant at the time. Just going through that process of making an argument on each section of a paper made a big impact on me.

Then in high school I had a fabulous AP US History teacher, and she really taught me about historiography. She brought in a professor from the University of Maryland who taught us about the historiography of slavery. You know, I thought of these things as just a bunch of facts and didn’t realize that there were so many different historians who disagreed about the history of slavery in the United States. I got to see one historian write “X” and then the next historian write “Y” and the next historian write “Z.” Through this, I really got to see history as a conversation among historians, and that was kind of a lightbulb moment for me. I learned not just about history as a collection of facts, but about historiography and history as a collection of arguments by different scholars.

You’ve already answered this question a little bit, but could you expand on how covering the Supreme Court inspired you to study law?

I was working for the Baltimore Sun at the time, and I really thought, after covering that Supreme Court case, “I’m going to go to law school, and I’m going to be the next Anthony Lewis or Linda Greenhouse.” Anthony Lewis covered the Supreme Court when I was younger and really showed the world that journalists should write about the Supreme Court in a very knowledgeable but very accessible way. He wrote one of my all time favorite books, Gideon’s Trumpet, and I had read that book about the case of Gideon v. Wainwright (1963). I wanted to be able to write about the Supreme Court in that way, both from having that J.D. background, but in a way where a person without a J.D. could understand it. I think in some ways, I’m still trying to do that. I’m trying to write books that speak to different scholars but also speak to an audience of nonlawyers and nonscholars. Just to tell a good story so that people will keep turning the page and will want to read more about why an individual or a group of individuals or a case may have fascinated me and why it might fascinate them.

You ended up clerking for Judge Dorothy W. Nelson. What was that experience like, and what did that opportunity teach you?

It was amazing. Judge Nelson taught me a lot of things. I could go on and on and on about her. She’s still alive. She’s still a force of nature. She still read my most recent book, and she’s in her 90s, and still has boundless energy.

Judge Nelson taught me there was a way to disagree without being disagreeable. And she was an incredible coalition builder on the Ninth Circuit. I used to call her “tea and cookies” diplomacy, She would set out a tray of cookies. She would ask people to have tea or something to drink, and she would sit in her office. She taught me that the law didn’t always have to be this adversarial, at each other’s throats kind of process. And that even if somebody might be more liberal or more conservative, you could find some common ground in figuring out the best interpretation of the law. And she is just a wonderful person with wonderful stories, and just a great mentor to me. She also was one of the first women dean’s at a top 25 law school, at the University of Southern California School of Law. She hired Erwin Chemerinsky, the great constitutional law scholar, at USC. So she really showed me, also, how fulfilling an academic life could be, and that the life of a law professor could be just such a rich one. She is still just a great exemplar and role model for me, and a mentor, and somebody whose opinion I value very much.

It was a wonderful year, and I’d also neve lived in Los Angeles before, and I really loved living in Los Angeles. It was such a great place to live and just a fun year. And I just feel so lucky to have clerked for her and to have clerked on the Ninth Circuit, and clerked in that courthouse with so many talented judges, but also with other talented clerks. Not just in my own chambers — both of them were super talented — but also all the law clerks in the other chambers who I got to know really well. And that was a part of the richness of the experience, that I got to rub shoulders with all these great judges, just to meet them on a personal level was really neat. And I learned a lot also about appellate advocacy, and about the quality of appellate advocacy. I had this idea that everybody who argued for the Ninth Circuit was the best possible appellate advocate, and that often wasn’t the case. The caliber of advocacy really varied depending on who was arguing, and it was rich. It was a fun time.

I got more confident in areas of law that I didn’t know a lot about. There were certain areas of law that I didn’t feel as confident in, and being a law clerk forces you to become more of a generalist. I’ll never forget having to write a memo about immigration law which I knew nothing about, and we called one of my friends who was clerking for one of the judges who was an expert on immigration law. I just wanted to make sure I wasn’t screwing it up. There was a lot of importance as a law clerk in getting it right. It was not really about liberal or conservative, but about: Did you get the law right? And did you apply the law right? That was a big concern for me, no one wants to make a mistake in a memo to a federal judge. And so there was a big premium on getting it right — and not with a political valence. And that was really refreshing to me, too.

Let’s go back to this: Why were you writing books about baseball? Just because you loved sports journalism?

My first book was basically my college honors thesis rewritten into a narrative. So my honors thesis in college was about the Homestead Grays, the Major League baseball team that played in Washington D.C. And I thought it would make a good book if I rewrote it into more of a story than I wrote the thesis as. So I did that in the nine months after I was done with my clerkship, actually, and then I worked at a law firm for a few years.

And I’ve always, ever since I was a sports writer, wanted to write a book about Curt Flood, and his fight for free agency in professional sports. And I thought he was a lot like Clarence Earl in Gideon’s Trumpet, this kind of “one man takes on the establishment” story. I kind of pitched it as baseball’s version of Gideon’s Trumpet and while Gideon wins and Flood loses, he ultimately opens the door for other people. And it was in the course of writing that Curt Flood book that I started to use the justices’ papers for the first time. Harry Blackmun’s papers had just opened up at the Library of Congress and other historians told me, “The journalists have mined the papers for everything they can about Roe v. Wade, you should come down,” and I went down, and I was really hooked. I mean, Blackman was a pack rat; he saved everything. He even saved slips of paper from Potter Stewart that said “Reds 3 Mets 2” in a World Series playoff game while they were on the bench.

His papers were really rich, and it just showed me a different way of looking at a Supreme Court case and how an opinion develops based on the drafts and the correspondence and the conference notes, and everything else that are in the justices’ papers. I got kind of hooked on using those primary sources and then the justices’ papers as a way to write and think about constitutional law and have really been doing it ever since.

As you said, a lot of your work comes with a focus on the individual work and lives of specific justices or clerks. Why have you focused on the personal stories of the law world?

That’s a great question. I think I’m really interested in how people network and create networks. People like Oliver Wendell Holmes and his clerks, and how Felix Frankfurter in selecting clerks — they were known as secretaries at the time — really was able to create this network of liberal lawyers entering government service and those impacts on American law. So I am interested in those personal stories. I think it’s partly because of my storytelling background as a journalist, but I’m also interested in how those individuals are more able to promulgate their ideas.

I agree. I’m not a theorist. I’m not a constitutional theorist in the way that John Hart Ely and Alexander Bickle and Bruce Ackerman were and are, but I am interested in how different people are able to promulgate their ideas and multiply those ideas across space and time. I’m interested in the way Holmes and Brandeis influenced Frankfurter and really how Frankfurter influenced a whole other network of people. It’s like throwing a stone into a pond, so it’s not just their individual stories, but how what they stood for, and who they worked with, have influenced a bunch of other people.

In telling those stories, how do you make sure that they’re digestible? That they’re rich and nuanced for legal experts, and also understandable for everyone else?

It’s hard. I mean, first of all, I have non-lawyers read the book, in addition to having my lawyer friends read the book. But I also just don’t want to bore the reader. I feel like if I’m bored, then the reader is bored. And so I always ask myself: “Can I make this divergence into this person’s story? Or am I going to interrupt the flow of the narrative? Can I introduce this minor character? How many paragraphs can I spend more on that person’s life, in summarizing that person’s life, before I move on with the story?” And I think those are the kind of decisions that any writer struggles with, not just a lawyer, but I just try not to be boring and keep people interested.

I do think people are interested in how people achieved greatness and how people got to where they are. And so some of the background stuff is interesting, but not too much background. And I think the cases, too, you want to put the people front and center. Who are the litigants, who are the lawyers? How are their lives affected by the case? Instead of just, “What was the court’s holding?” and “What was their reasoning?” To try to make it read less like a law school case brief and more like an interesting narrative that somebody’s willing to read.

You’ve told a lot of stories about different people in the legal world. What made you so interested in Justice Frankfurter?

I graduated from law school in 1999. And probably a year and a half after that, some of my friends were clerking on the Supreme Court of the United States. I had one over for dinner that night with my family. And he got up in the middle of dinner, and he said, “I have to go.” I said, “What do you mean?” “I have to go,” he said. “I have to go back to work.” And this was obviously late November of 2000, when the 2000 election was hanging in the balance, and my jaw hit the floor.

I was really so disappointed that the Supreme Court chose to intervene in the 2000 presidential election and write the opinion that became known as Bush v. Gore. I had really lost faith in the Supreme Court as an institution, and believed that the Supreme Court had really involved itself in what was essentially a political decision and one that was reserved to the state of Florida, on how to count its votes. And the Supreme Court’s rationale in Bush v. Gore was an equal protection rationale that the Court said was good for this train only. Well, that’s not how the Court operates. Right. The Court writes decisions of general applicability, and it’s not like a boxing referee in an arena just raising one side’s hand or the other. And I just lost my faith in the institution.

So flash forward a couple of years later; I was writing my first law review article about the Rosenberg case. And a lot of people who follow the Court closely were really upset with the court’s refusal to take the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and to hear that case on the merits. They heard it at the 11th hour right before the Rosenbergs were executed, but Felix Frankfurter and Hugo Black, in particular, argued to their colleagues that the Court should have taken the case from the get go and Frankfurter wrote a dissent after they’d been executed, and he wrote that “History has its claims.” He was speaking to his law clerks and to his former students who were either litigating before the Supreme Court or working in the Solicitors General Office.

He was basically telling them, “Don’t lose faith in the rule of law. We got this one wrong, but don’t lose faith.” And in many ways. Frankfurt’s philosophy of judicial restraint started to speak to me after Bush v. Gore and after another case called City of Boerne v. Flores in 1997, in which the Supreme Court eviscerated Congress’s power to enforce the 14th Amendment. Those two decisions really showed me that the Supreme Court was becoming too powerful, and that it was aggrandizing its own power at the expense of the other branches of government, as well as the states. And that the Court really believed in this false idea that it had the last word on the Constitution.

I think Felix Frankfurter’s life and career really speak to those things. He was that liberal nominee to the Court in 1939, perceived to be this conservative villain when he goes on the Court, and certainly by the 40s and during the Warren Court years, as this villain of the Warren Court. But I think he recognized that the Warren Court was a liberal aberration, and that the Supreme Court of the United States is an inherently conservative, backward-looking institution that relies on a lot of precedent in history to decide cases, so by necessity, it’s going to be backward-looking. He was encouraging people to try to solve their problems through the state and federal Democratic political process. And that spoke to me after Bush v. Gore.

So I thought, “Has Felix Frankfurter fallen so out of favor, this justice of liberal judicial restraint, that no judicial biography had been written about him?” So I decided that I would write it. And since Bush v. Gore — there are several decisions — since Shelby County v. Holder gutted the Voting Rights Act, since the Court tried to chip away at the Affordable Care Act, and since the overturning of Roe v. Wade, I think Felix Frankfurter’s reputation looks a lot different in 2023 of the set than it did in 1975, when William Brennan was in his ascendancy, when he was the leading justice on the court. And he was sort of the champion of judicial supremacy, and this idea that liberals could always cobble together five votes on the Court. And those days are gone, and they’re not coming back. And so now I think liberals are starting to recognize that, and Frankfurter’s ideas about judicial restraint have some purchase in 2023.

Did you uncover any unexpected things while writing the book?

I did. One thing that really interested me that I uncovered was that there were two very prominent Jewish figures in America — Arthur Hays Salzburger, who was the publisher of the New York Times, and Henry Morgenthau Sr., — who let it be known to President Roosevelt not to nominate Felix Frankfurter to the Supreme Court in 1939 because they were worried about the rising tide of anti-semitism, both in Europe with the rise of Hitler, but also in the United States of America. And that Frankfurter’s nomination would instigate more anti-semitism, and that really was jaw-dropping for me. And likewise, that same crowd of people was advising Roosevelt not to let more Jewish immigrants into the country when the Nazis were invading Europe, and that also was surprising to me.

Those were two big ones. I’d say my best find in terms of documents was related to Frankfurter’s best or favorite law clerk, Alexander Bickle. He was a big-time constitutional theorist at Yale. He coined the phrase, “the counter majoritarian dilemma.” Bickle was Frankfurter’s law clerk during the 1952 term, the first time that Brown v. Board of Education was argued. Sadly, Bickle died in 1974 of cancer, and I kept thinking to myself, “If I could only have a conversation with Alexander Bickle about Frankfurter as I’m writing the book.” And I went to the FDR library and found Joseph Lash’s work, who edited Frankfurter’s diaries and wrote up a 100-page biographical sketch in 1975 arguing the Frankfurter became uncoupled from the locomotive of history given how liberal the Supreme Court was — it’s a great essay.

But Lash had done a bunch of interviews, and he had notes, and shortly before Bickle died of cancer in 1974, he had done an interview, and those notes were preserved in the FDR library. And it was basically a transcript of everything Bickle said, and I felt like he was speaking to me from the grave about Justice Frankfurter. It really helped me think hard about different points of Frankfurter’s life, and I kept going back and reading that interview over and over again, almost like I was calling people from the dead. But reading that interview was almost like speaking to him from the dead or hearing him speak to me from the dead. And it really was an incredibly helpful document to me.

What’s your favorite anecdote about Justice Frankfurter?

I’m going to kind of answer your question. I have a couple. But one of my favorite anecdotes about Justice Frankfurter is this: In 1948, he hired the first African American law clerk at the Supreme Court, a man named William T. Coleman, who became Gerald Ford’s Secretary of Transportation. And Coleman’s co-clerk was Elliot Richardson, who was his best friend from Harvard Law School. Richardson became Nixon’s Attorney General during the Watergate Saturday Night Massacre. And one day, the Supreme Court cafeteria was closed, and the law clerks decided to go to the Mayflower Hotel for lunch. And at the last minute, Elliot Richardson, who again was best friends with Bill Coleman said, “Hey, Bill, I’ve got too much work, let’s go eat at Union Station nearby.” And Elliot Richardson did not have too much work. Frankfurter did not work his clerks that hard.

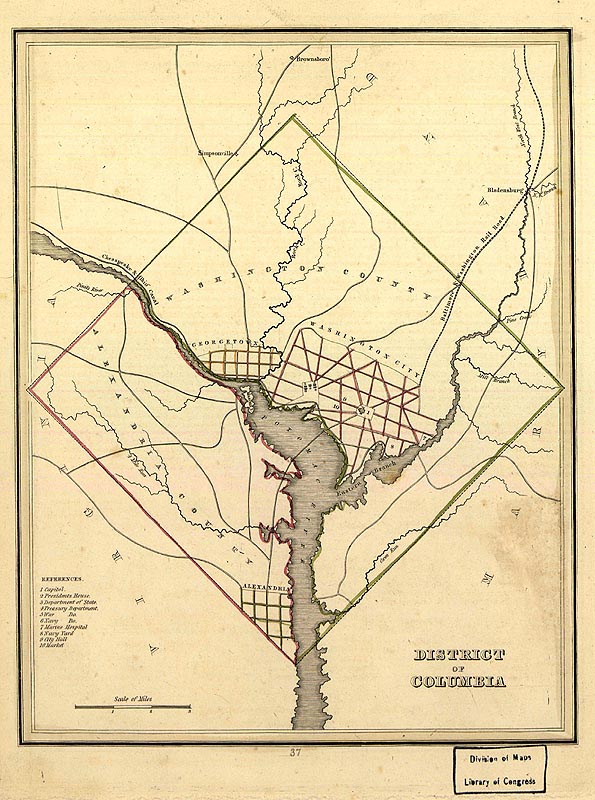

But the Mayflower Hotel did not serve black customers in Washington D.C. in 1948. Union Station was the only place in Washington D.C., because it was owned by the federal government, where a black person and a white person could have a meal together, and it wouldn’t be illegal. And Frankfurter, when they came back from that lunch, had tears in his eyes because, of course, he understood what Richardson was up to. And then, more than that, I was really struck by this memo that Bill Coleman had written Frankfurter at the end of his clerkship about graduate school segregation cases that were coming up before the Supreme Court. The NAACP was suing the southern states that had all-white law schools but no law school for black students, and tried to admit black students in the state of Texas, for example. And Coleman wrote this really detailed and passionate memo to Frankfurter about the case that I really think helped Frankfort to think about the case. In fact, I know it did, because Frankfurter passed along the memo to several subsequent clerks and even to Bickle himself when he was clerking for Frankfurter.

So it was incredibly influential for Bill Coleman to break barriers, kind of as the Jackie Robinson of Supreme Court Clerk, and overcome all kinds of discrimination, but also, the way he was able to provide a perspective that Frankfurter wouldn’t have otherwise had about separate but equal and about how to defeat the separate but equal doctrine. And at the end of his clerkship, Frankfurter wrote a letter to Bill Coleman, and he said, “I bet on you.” And, of course, it was a good bet. Because as I said, Bill Coleman became, I think, the second black member of a presidential cabinet.

What’s your favorite piece of serious wisdom from Justice Frankfurter?

My favorite piece of serious wisdom is that people shouldn’t seek social and economic change at the Supreme Court of the United States, that trying to affect change through the Supreme Court is a fool’s errand, and they should invest themselves in the democratic political process. I mean, think about if people worked as hard on trying to elect US senators and US congresspeople and engage themselves as much in the legislative process, as they did in following Supreme Court cases. I just think that trying to seek change through the Supreme Court is fool’s gold. It’s evanescent, and I think Frankfurter was right about that, that the way to create more permanent lasting change is through laws, that it’s much harder to overturn a federal law, for example, than it is to overturn a Supreme Court decision based on the Constitution.

Yeah, people are feeling that one right now, for sure.

Yeah. In a post-Roe universe, they’re feeling that one.

Is there anything else you think that young people should know about Justice Frankfurter?

He was really fearless, Hannah. As a young lawyer, he was willing to take risks and to take on powerful people. He took on the Attorney General of the United States, A. Mitchell Palmer, over the conduct of the Palmer Raids, the round up and deportation of radical immigrants that was led by a Young Justice Department official named John Edgar Hoover. And he, along with a bunch of other people, signed a document accusing A. Mitchell Palmer of unconstitutional conduct. He championed the idea that Sacco and Vanzetti had not received a fair trial and took on not just the Massachusetts trial judge, but the State Supreme Court of Massachusetts. He took on the anti-semitic president of Harvard College who wanted to institute a 15% quota on Jews at Harvard. He took these people on; he was willing to stand up for what he believed in, and yet, became a Supreme Court justice.

I think sometimes people say, “Well, the way to get ahead is not to do controversial things.” I think Frankfurter stood up for what he believed in and was willing to take on fights, even if he lost some of those fights. And he did — Sacco and Vanzetti were executed, A. Lawrence Lowell found another way of reducing the amount of Jewish students, namely geographic diversity, and a lot of people did get deported by A. Mitchell Palmer, but Frankfurter saved 17 of the 23 people he represented in a federal court in Boston.

So I think he was willing to lose. I mean, he backed Robert LaFollette, a third party candidate, for president in 1924. Walter Lippmann, his friend and fellow New Republic contributor, said, “You’re throwing away the election.” And LaFollette said, “Walter, my interest isn’t just what happens in 1924. I care what this country looks like in 1944.” And so he was willing to also play a long game, and I think that’s a good lesson for liberals with a Supreme Court that’s stacked against it. That they should just be willing to keep fighting on all fronts, and play a long game.

One more thing I just want to say: I think Frankfort has a reputation, some of it deserved, as pedantic and thin-skinned, and as somebody who alienated some of his colleagues, but he also had a lot of really close colleagues on the bench. He was incredibly close to Robert Jackson, to John Harlan, to Harold Burton, to Owen Roberts, to Sherman Minton, and his relationship with Hugo Black is one where — I know you’ve had Noah Feldman on the podcast, and I have an utmost respect for knowing his work — I really just reject the notion that they were antagonists o scorpions. They had a lot of disagreements, but they were close. And when they needed each other, they were there for each other. And it was Frankfurter and Hugo Black in Brown v. Board of Education who were helping Earl Warren achieve unanimous results. And they were on the same side in the Rosenberg case. When Frankfurter wrote the opinion in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, saying that Tuskegee had drawn its city boundaries to exclude that black voters, the first person he gave that opinion to was to his friend Hugo Black, to make sure that Black was okay with the opinion before he circulated it to the rest of the justices. So they had their ups and downs, but I don’t think they were scorpions or antagonists. I think they were intellectual adversaries but also friends.

Something that was so entertaining about Scorpions was all the tension, but sometimes I wondered if it was all played up a little bit.

Well, there was tension. Frankfurter and William O. Douglas hated each other. And it was mutual. The two people that Frankfurter hated most in his lifetime were William O. Douglas and Joe Kennedy Sr. Joe Kennedy Sr., of course, spread a lot of anti-semitic filth about Frankfurter during the New Deal. And William O. Douglas was Joe Sr.’s best friend, and they just didn’t get along when they were on the Court together. Frankfurter thought that Douglas was out to run for president first and be a Supreme Court justice second, and Douglas thought that Frankfurter was overbearing, and not half as smart as he thought he was. And they both have a point about each other. So they just clashed, and that clash became both personal and professional, and they just never could really reconcile.

So of course, there was a lot of drama. I think what Noah points out is that whenever you have four justices as smart as Hugo Black, Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, and Robert Jackson, you’re going to have clashes, because they’re all really strong personalities, and they’re all incredibly brilliant. With strong personalities and brilliance, they’re going to butt heads. I just think that was inevitable. I think it’s a product, really, of their brilliance. I put those four up against any four justices that have ever served on the Court at one time. Just to have that many brilliant minds on the Court at one time was remarkable, so I think that’s why you had a lot of drama. One of my other colleagues besides Noah calls them the four prima donnas. I think that’s a really good way to describe them.

In Noah’s book, I think it said something about Douglas falling off a horse, and someone made some comment like “Oh, did Frankfurter push him?”

Yeah, I think that stuff gets played up. But I hear you. I mean, Frankfurter was from New York City. The last place he’d be in the world would be on a horse. But that’s neither here nor there.

Well, I feel like in the Pacific Northwest, at least in Washington, there’s a particular fondness for Justice Douglas and horses.

Justice Douglas, he’s from Yakima. And he really was a champion of the outdoors. He saved the C&O canal along the Potomac River that goes all the way from Washington, D.C. out into Western Maryland. I mean, he loved to hike, he would hike very fast. He was a great outdoorsman and a great champion of the environment, and I admire him for those things. But I think Justice Douglas and Frankfurter were just so temperamentally different. Frankfurter was such an extrovert, and Douglas really was an introvert. He was not a people person. He was a little bit misanthropic. Frankfurter just loved and thrived on his interactions with people.

As someone who lives in Seattle, I think Justice Douglas really at the end of the day was just quintessential Washingtonian, Seattle freeze.

It’s so interesting that you say that. There’s a scholar that’s been working on a book about Justice Douglas for a really long time named David Denelski. I really hope he publishes it because I think it’s going to be a great book. He wrote a really great article in the Journal of Supreme Court history about how Justice Douglas got nominated to the Supreme Court, that I highly recommend if you’re interested in Justice Douglas.

You’ve written a lot of books. What does your typical writing process look like? And how do you make time for writing while also teaching?

First of all, writing is an essential part of my job. I love teaching students. I learn so much teaching constitutional law and constitutional history. But half my job is to write, and I love writing. Writing for me is like getting a good workout every day. So I try to exercise that part of my brain every single day. Even if it’s just a couple of sentences, even if it’s just adding a couple of sources to the piece of writing, I’m always thinking about, “What do I need to work on today in my writing?”

And then one thing that I’ve learned to do, and I definitely did it for this book, was to research and write chapter by chapter. If I’m working on a chapter, let’s say I’m on court packing, and I’m totally immersed in all the sources about court packing, I’m gathering everything I can get that I need to write a court packing chapter from Frankfurter’s perspective, and then I write it up. And then I go on to the next event in 1939. It is that kind of process that helps me to get myself into the primary and secondary literature in a way that I can just kind of bang out that chapter, and go through some revisions, but not let perfect be the enemy of the good. I’m trying to get a draft in a way that I think is good enough, for now. And then keep going. Rather than rewrite and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, because I would never get finished with the book. So that’s what I’ve tried to do on my last few books is research and write chapter by chapter.

You also teach constitutional law seminars, so I have to ask: What are your thoughts on the Court’s current ideological divide? What cases are you watching this term?

I’m watching the affirmative action case. I’m watching the 303 Creative case involving whether somebody can essentially, because of her evangelical beliefs, be exempt from the anti-discrimination laws. Does it violate her free speech in creating websites for people? So I’m interested in how those cases are going to come down. I’m pretty certain that affirmative action is not going to be constitutional any longer. What I’m interested in is, it’s going to be really difficult for the Supreme Court to enforce that decision. I think it’s going to look a lot like Engel v. Vitale, which is the prayer school case, or even to some degree Brown v. Board of Education, where the Supreme Court is going to make a pronouncement that colleges and universities are not going to be able to use race in the admissions process. And then I think it’s going to be kind of a whack a mole situation, where colleges and universities are going to change their processes in such a way that will still create diverse classes of people, maybe not taking race into account in the same way, but they’re going to, I think, successfully evade the Court’s decision. I’m interested, not just in how the cases come down, though, I’m interested in what they say. I’ve really found Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to be a refreshing voice on the court. Her comments at oral argument about the original meaning of the 14th Amendment, I found to be both strong and much needed. And I love that she’s bringing that perspective to the group. So I’m interested to see what role she plays in advancing those beliefs about the original meaning of the 14th Amendment.

On the podcast, we’ve been focusing most of our episodes on the affirmative action cases, and we were really excited when we got a college admissions officer to talk to us about preparation for the decision.

By the way, one of the great things about Georgetown is we have a Supreme Court Institute, and they mooted both sides of that affirmative action case. Of course, I’m only allowed to go to one side’s moot so as not to violate confidentiality. But I mean, it was really spectacular to see that case mooted in the days leading up to the oral argument, and we spent most of our semester talking and thinking about the affirmative action cases in our Con Law II class.

The interesting thing about the cases is I think it’s bigger than affirmative action. Regardless of how the case comes out, I think that the meaning of the 14th Amendment is up for grabs. And I think that transcends affirmative action. And so this is why I think that Ketanji Brown Jackson bringing the original meaning of the 14th Amendment to the forefront is so important, because the meaning of that amendment is up for grabs.

I have one final, very important question. Why do you think that young people should pay attention to the courts and engage in the law? And are there specific areas that you think it’s important for high school students to focus on?

I think it’s important for high school students to become engaged citizens. And that’s informed about how their state governments work, how their local governments work, and how the federal government works. And that’s true of all three branches — of the House and the Senate and the Supreme Court of the United States. And because, for better or worse, the Supreme Court has played such an outsize role in some of our policy debates recently, I think high schoolers need to be educated about the Supreme Court. And because the voting age is 18, they’re going to be voting in presidential elections soon, and presidents choose justices. So that part of civic education is so important so they can become informed voters, and they can just see how the Supreme Court affects their daily lives, and how the Congress and how city government affects their daily lives. And so I think it’s worth reading SCOTUSblog, or listening to the Strict Scrutiny podcast. I know that’s a favorite podcast among some of my law students and me. And, I think that kind of podcast would appeal to young people as well, because there’s a lot of humor in it.

We’re thoroughly obsessed with Strict Scrutiny. We’ve been trying so hard to bring them on our podcast.

I was on a Zoom panel with one of the members of Strict Scrutiny and then two of the others are coming to give talks at Georgetown to the faculty this year. So we feel really privileged, and they’re all great. They’re a great podcast. Those are the types of ways to get into learning about the court that don’t involve necessarily reading a Supreme Court decision. The decisions now are long, they’re technical, they’re often written by law clerks and aided by Westlaw. They’re too long. They’re too technical. And I think that’s where reading SCOTUSblog, or listening to the Strict Scrutiny podcast, or following people like Larry Tribe and other academics on Twitter, can really allow young people to begin to engage with the Supreme Court of the United States. And then they should all go to law school and apply to Georgetown!